by Dennis U. Eroa

BY GAME’S end, Virgilio “Billy” Abarientos still wanted to make those nifty passes and zigzag past defenders to make an easy basket. His opponents and a sprinkling of wide-eyed young and elderly fans were mystified by this sweating man in his late 60s, who was able to keep up with the punishing pace of full-court basketball inside a sweaty indoor court called the Triangle. It seemed that Abarientos had the strength for another game against foes young enough to be his children.

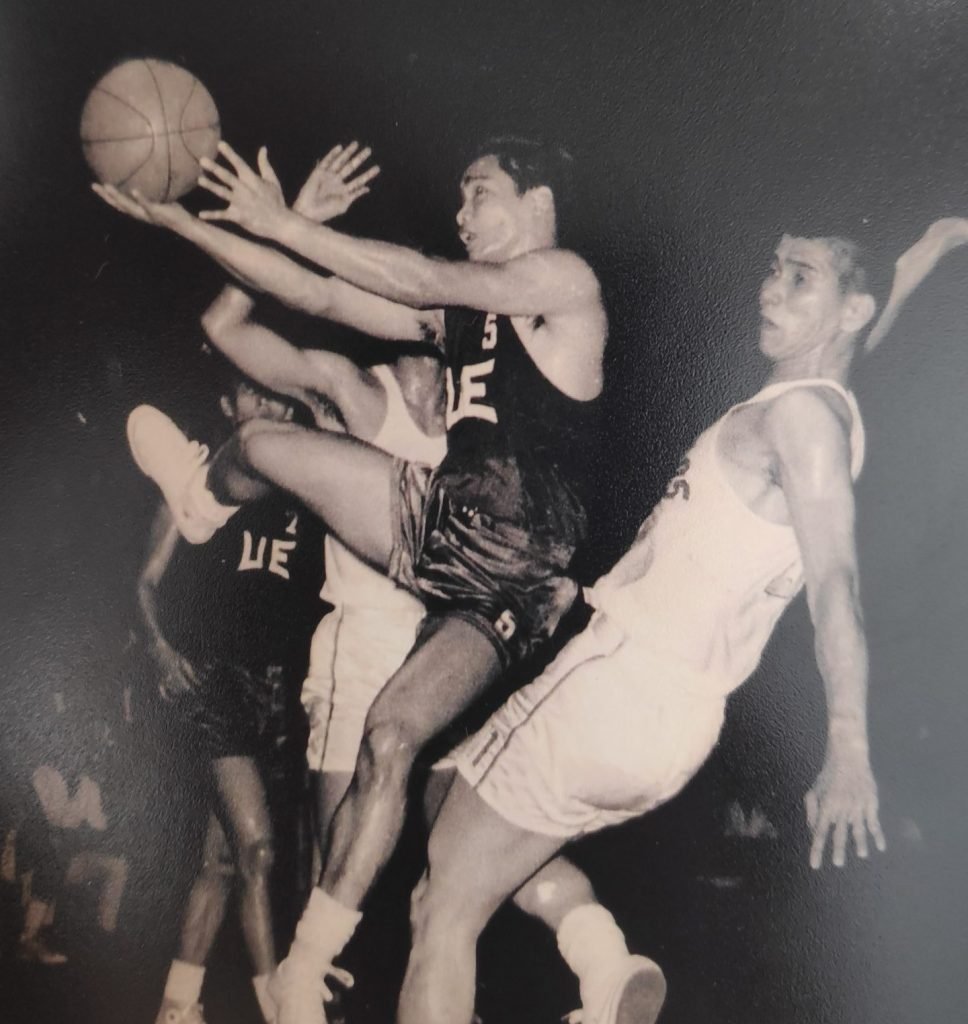

Every afternoon, Abarientos, who once sowed terror in the backcourt playing for the legendary University of the East under Baby Dalupan before trying his luck to professional and amateur teams, was a thrill to see as he dribbles wisely and glides to the basket with the intensity of a Red Warrior hunting for a kill.

Very few among the enthusiasts, however, knew the colorful and exciting life of Abarientos, who retains not just his youthful looks but his ability to maintain his sense of humor and interact reasonably. Hardly adding a decibel to his voice, it was clear that Abarientos remains in control.

Nowadays, though, Abarientos a grandfather of ten and uncle of the more famous and former Philippine Basketball Association Most Valuable Player Johnny “Flying A” Abarrientos (note the spelling) is no longer a regular at the Olongapo City court not solely because of the pandemic but because of failing eyesight due to glaucoma, an eye disease which damages the optic nerve and cause gradual or sudden loss of vision.

To go around, Abarientos needs to be assisted by his youngest son Veinjie, a Physical Therapist, who graduated from the University of the Santo Tomas. The 28-year-old Veinjie is Abarientos’ constant companion at their residence in Marulas, Valenzuela or whenever they unwind at the Subic Bay Freeport Zone.

Things started to change when during a regular game Abarientos wasn’t able to telegraph a pass from his son Veinjie. Normally, the elder brother Abarientos would get the ball and attack the basket or find the open man. The scene was repeated the next outing.

“I thought my reflexes are gone because of my age, that my legs are gone,” said Abarientos, who was already 68-year-old by that time. “It turned out my vision is problematic.” The doctor at Makati Medical Center said the problem started years back but was left untreated. Abarientos can still read but the loss of vision can no longer be reversed.

Now 75 and most of his UE, Crispa, and Universal Textiles (Utex) and Carrier and national team contemporaries gone, Abarientos dubbed as, “Haba-Haba” by the iconic sportscaster Willie Hernandez looked with fondness a career that started during his elementary days at the Marulas Elementary School. He studied high school at Victorino Mapa in Manila.

“My father Burgos was a basketball player. I played for Marulas and was instrumental in helping the small school compete with the bigger schools in various Manila tournaments ,” recalled “Haba-Haba,” a well-loved figure in the community which led him to be given Gawad Parangal for sports excellence by the Valenzuela City government led by then-Mayor now Senator Win Gatchalian.

Abarientos said his father regularly brought him to the Rizal Memorial Coliseum to watch members of the national team like Caloy Loyzaga, Lauro Mumar and others do their court wizardry, but he was mesmerized by the gazelle-like moves of Antonio Genato, a product of San Beda.

“I wanted to be like Genato because he was small but so fast,” said Abarientos. Genato, who hails from Valenzuela City, donned the country’s colors in the 1952 Helsinki and the 1956 Melbourne Olympics but he became a byword when he skippered the Philippine team which bagged third place in the 1954 World Championships in Rio de Janeiro. That finish remains unmatched in the history of Pinoy hoops. Understandably, Abarientos, whose eldest daughter is married to Allan Caidic‘s brother Ronnie, would try to strive or even better Genato’s playing style. Even during those years, Abarientos at 5-foot-4, seemed out of place when ranged against bigger and stronger foes but wait till he toys with the ball and jumps to contest the rebound or make an easy floater to confuse a defender. Abarientos perfected the art of dribbling.

“Hernandez called me Haba-haba because of my jumping ability,” chuckled Abarientos, who said that he wasn’t afraid of banging bodies with heavier foes. “Basketball is a physical game and one must be ready to take a hit,” said Abarientos. He likened the game to sabong (cockfighting).

“During my time, it is common for fans to bet on their favorite teams. It happens even today. Now we also have the ending game which adds to the excitement,” noted Abarientos, who also tried long jump in high school.

Abarientos said he was supposed to play for UST in the UAAP under the Big Difference, do-it-all center Loyzaga, but Dalupan lured him to UE. “Even If I’m not yet on the official lineup, Coach Baby brought me to Japan to various Japanese cities where we played exhibition games against collegiate teams . Naturally, I enrolled at UE.”

The result, of course, was three straight UAAP titles from 1966 to 1968 plus Intercollegiate crown for Abarrientos and the Red Warriors. He played with the likes of Robert Jaworski, Joseph Wilson, Rey Alcantara, Rudolf Kutch, Ernesto de Leon, Rodolfo Soriano, Johnny Revilla, Armando Yango, Manuel Acuna and Daniel Pecache.

“I got tired visiting Hong Kong and Taiwan as perks for winning so many titles while at UE,” said Abarientos.

What happened in the 1967 Universiade in Tokyo was forever imprinted in the memory of “Haba-Haba.” The Philippines was represented by UE bannered by Jaworski and Danilo Florencio. But Abarientos, the smallest among the players, played a pivotal role in the fifth-place finish of the nationals.

The score was tied in the dying seconds against Belgium and Abarientos was able to get the jump ball. Without hesitation, Abarientos heaved the ball near the midcourt. The buzzer shot was greeted with deafening roars from the crowd, assuring the Philippines of a fifth-place finish. Favorite US beat South Korea for the gold medal.

“Memorable game,” said Abarientos, who went on to play for Crispa under Dalupan in the amateurs. His Crispa stint, however, suffered a setback when he got embroiled in an alleged game-fixing scandal with other players. Abarientos, however, laughed off the accusation which temporarily setback his career and affected his family.

“Somebody was out to discredit me. My question is, I’m not even a star player how can I do that,” said Abarientos, who went on to play for Utex and Carrier in the pros. “Haba Haba” didn’t stay long in the PBA and he again played In the amateurs with distinction.

Upon retiring, Abarientos found work as a warehouse manager at Johnny Air Cargo. Johnny Air was established in 1984 by De La Salle U alumnus Johnny Valdes. JAC pioneered the industry in providing speedy, reliable delivery of packages between the US and the Philippines. Abarientos worked for 30 years as a manager.

“I am lucky to be given the opportunity to work for Johnny Air. The company takes care of its employes very dearly and I have no regrets spending the best years of my life with JAC,” said Abarientos as his face lit up with pride.

The pandemic disrupted the Filipinos’ sporting lives and cagers are very much affected. Not all players enjoy extremely high salaries, some are even jobless due to lack of teams or absence of tournaments. It is common to see pros and ex-pros in dire straights, resorting to taking new territories other than shooting the ball.

But “Haba-Haba” is one of the lucky few to brave the journey and escape destruction to gain a peaceful life. “It’s all about focus, discipline and your desire to achieve something.”

- The Wonderful Journey of Chino Trinidad - July 14, 2024

- On Yuka’s victory and the sad taleof athletes abandoning the country - June 6, 2024

- Quezon Titans: A Symphony of Grace, Speedand Strength; St. Clare Majestic - April 22, 2024