by Vince Juico

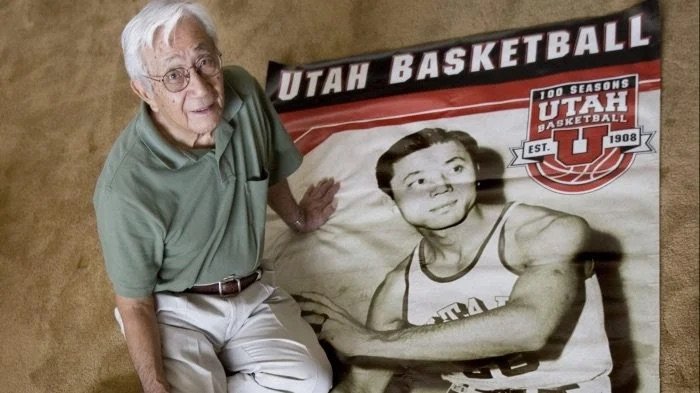

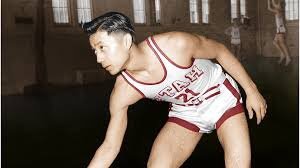

I came across Wataru “Wat” Misaka, the first non-Caucasian or non-white player to play in the NBA. He broke the color barrier in 1947, the same year baseball legend Jackie Robinson broke the color line in baseball.

Misaka was 5-foot-7 and was drafted by the New York Knickerbockers of the then BAA (Basketball Association of America), the forerunner and precursor of the NBA or National Basketball Association.

I always thought an African American was the first non-white player to play in the NBA. According to The Undefeated, “Because [African Americans] [Chuck] Cooper, [Nat ‘Sweetwater’ Clifton] and Earl Lloyd, who came along like three, four years later, they’ve always been considered the three trailblazers.”

Before there were backcourt lockdown defenders like Patrick Beverly and Tony Allen, Wat Misaka paved the way for them.

The Undefeated asks, “Who broke the color barrier for modern professional basketball? That would be Wataru “Wat” Misaka, a 5-foot-7 Japanese-American who in 1947 became the first non-white player in the Basketball Association of America, or BAA, the precursor to the NBA.

The Undefeated asks, “Who broke the color barrier for modern professional basketball? That would be Wataru “Wat” Misaka, a 5-foot-7 Japanese-American who in 1947 became the first non-white player in the Basketball Association of America, or BAA, the precursor to the NBA.

Overly simplified, Misaka broke an ethnic barrier in pro basketball just as Jackie Robinson did in baseball. Their breakthrough moments even occurred in the same year.”

As I was reading Misaka’s story, the film Unbroken came to mind. The movie was based on the incredible true story of Louis Zamperini, a former Olympian, who was captured by the Japanese, becoming their prisoner of war and forgiving his captors.

As I am writing this piece, crimes against Asian Americans continue to rise in the US. The Undefeated article continues to say, “Most people would be rightfully upset about a professional sports career ending because of racism in a contentious political climate. It’s unfair, unjust, un-American. But Misaka didn’t fight the decision.

To fully understand why, one must realize the Japanese concept of shikata ga nai, which translates to “it can’t be helped.” It’s a cultural philosophy and coping mechanism similar to a portion of the serenity prayer: “accept the things I cannot change,” so move on.”

“I think for some people back then, a person of color was a black person. If you were Asian, you were just a damn foreigner,” said Paul Osaki, the executive director of the Japanese Cultural and Community Center of Northern California.

The oversight of Misaka’s contribution is a microcosm for how Asian Americans often feel marginalized or neglected in national conversations about race. Of course, race shouldn’t be the only factor in determining legacies; production and performance are also pivotal.

Misaka played in only three games for the Knicks, averaging 2.3 points. How praiseworthy is that? That’s like saying Chris Dudley deserves more acclaim, Participation Trophy Generation Guy. Well, to quote Robert De Niro in the movie Heat, “There’s a flipside to that coin.”

I’ve had a healthy dose this week of amazing and incredible stories from Pawie Fornea to Louis Zamperini and finally, Wataru “Wat” Misaka.

- Svitolina wins 2026 ASB Classic - January 14, 2026

- Sports in 2026 - December 30, 2025

- Reap what you sow - October 31, 2025